South Carolina Regulators

by Randell Jones, December 2021

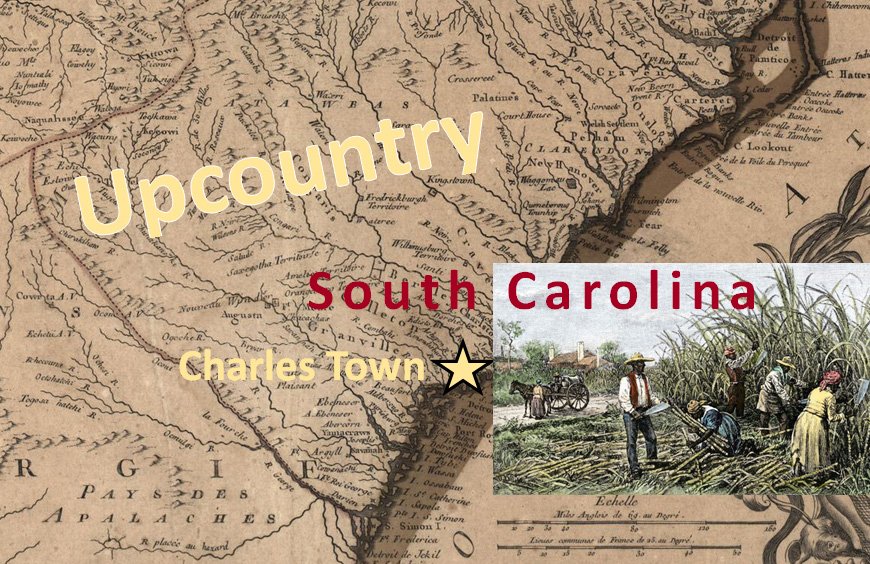

Among an estimated Upcountry population around 35,000 in the mid-1760s, 3,000-6,000 men participated in Regulator activities.

During colonial times, the planter classes mostly stayed in the coastal regions of South Carolina as they did in North Carolina and Virginia. They were part of the Atlantic world, connected by oceans with trading partners in European markets with some connected to colonial ports in the Caribbean Sea as well. These New World neighbors of the 13 American British colonies were earlier colonial outposts of French, Dutch, and British exploitation of indigenous islanders, using enslaved labor to turn large profits. This practiced approach to colonialism expanded into the coastal Carolinas during the 1600s and early 1700s. Of note, Charleston, South Carolina, originally began in 1670 as an outpost to provide firewood and timber to Barbados, whose all-consuming sugar industry had denuded the island of trees. (See Charles Town Landing State Park.)

In the backcountry of South Carolina, however, many more settlers were small farmers seeking land enough to establish a homestead, although certainly a percentage were well-heeled persons seeking to secure large tracts of land. For all these settlers, land was the ticket to prosperity. Following the Cherokee War of 1759-1761, settlers immigrated into the Upcountry of South Carolina, many arriving along the Great Wagon Road through Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley and North Carolina’s piedmont. They did so with some confidence that after the issuance of the Proclamation of 1763, the dangers of their moving into former Cherokee landswere greatly diminished. These were first- and second-generation

American colonists of different origins—Scots, Irish, German, French, Swiss. They divided themselves also by religion: Quaker, Presbyterian, Baptist. Accordingly, expectations of how life ought to be lived varied from one community to another. For example, cattle raising was popular with the Scots and the Germans who occupied large tracts of grazing pastures called “cowpens.” People of like cultures tended to gather together and not to communicate so often with the people of other scattered communities. This situation helped make the region attractive to the bandits, cattle rustlers, horse thieves, and burglars who preyed upon the isolated communities throughout the sparsely settled region.

Outlaws ran amuck across the Upcountry, stealing horses and cattle and in the process also murdering people. All courts of justice were in Charles Town on the coast, too far away to be of any help. The good citizens of the Upcountry, not being able to secure any relief from the remote government, took their mutual safety into their own hands and formed a band of rangers they called Regulators.

With good and honorable intentions initially, the Regulators set about hunting down notorious horse thieves and robbers, administering the traditional punishment of 39 lashes with a whip and a warning that harsher penalties awaited them if they were caught again. Sometimes, they escorted the villains out of the region. Others they took on the difficult 200-mile trek to Charles Town for official justice, at the risk of being attacked by the accomplices of the rogue they had in hand.

These bands of Regulators, operating separately, sometimes acted on old grudges and animosities as much as at apprehending lawbreakers. After some time, they excited the citizenry concerned about their extra-judicial practices—the punitive tarring-and-featherings, the whippings. The concerns grew as the Regulators began, as well, to address with whippings the moral failings of others—in their opinions—including “unruly women” and those the Regulators thought “idle.” Moreover, the outlaws themselves banded together to resist the Regulators and soon the Upcountry was caught up in the commotion of a seeming civil war between “good guys” and “bad guys,” both sides acting excessively.

In 1766, Royal Governor Lord Charles Greville Montague acted decisively, but not helpfully. He commissioned Joseph Scoffel to act on behalf of the government to moderate the Regulators in the Upcountry. Scoffel (also Scovil, Coffel, and Scophil) was a man of questionable character, he later convicted of hog stealing. Calling himself “colonel,” he banded together some of the outlaws and others offended by the Regulators’ actions. He acted officiously, under the royal standard, as if the colony were under attack. Scoffel’s moderators set about confronting the Regulators, doing so in the most scurrilous manner, confiscating provisions from farms, and impressing horses. He even arrested some prominent men among the Regulators and carried them off to Charles Town.

Scoffel’s “moderators” included bandits and outlaws.

Detail from painting by Richard Luce (RichardLuce.com)

“Colonel” Scoffel was a man of questionable character

(a representation)

The two bands of men roaming across the Upcountry were nearly set to spark an all-out shooting war, when the government withdrew its support for Scoffel’s efforts. The residents could also see that no good would come from fighting each other, so they helped defuse the tension. The two groups pulled back from each other, and a civil war was averted. Nevertheless, Scoffel had made his mark. General William Moultrie later remembered Scoffel as “a man of some influence in the backcountry, but a stupid, ignorant blockhead.”

The Upcountry inhabitants represented three-quarters of the colony’s white population, yet they had only two representatives in the Assembly. In 1768, the Regulators marched to the polls and elected six candidates to the Assembly. And with the passage in 1769 of the South Carolina Circuit Court Act, courts were established at Ninety Six, Cambridge, Camden, and Orangeburg. With that accomplished, the Regulators disbanded. Still, animosities lingered among the citizenry who had taken sides with and against the Regulators.

Ninety Six National Historic Site interprets colonial life in the South Carolina backcountry in the latter 1700’s.

As the American Revolution approached, the whig leaders among the planter class on the coast were concerned about the men in the Upcountry perhaps siding with the loyalists. Some writers have claimed a simplistic division, that the Regulators became whig rebels and the “Scovilites” became tories. But the matter of choosing sides was much more complicated than that. Former Regulators sided with and against the whigs. Those who had opposed the Regulators sided with and against the tories. Sometimes it was a matter of personal grievances established against a neighbor during the Regulator uprising. Sometimes, and especially among the aspiring planter class in the Upcountry, men favored the side which offered them the better opportunity for rank and privilege and power. Moses Kirkland, Robert Cunningham, and Thomas Fletchall were Regulators themselves or supported the cause, but they sided with the loyalists in the American Revolution. They did so to the consternation and disappointment of the coastal whigs who grieved the lost potential of their influence among those in the Upcountry in supporting the coming revolution. •