Terror in the Backcountry, 1771

by Randell Jones

Spring 2021 is the 250th anniversary of some notable events for America’s later nation-building efforts. Known as the War of the Regulation, these consequential events are unique to North Carolina and precede the Declaration of Independence by five years. Tensions in the North Carolina backcountry over many years, at last, came to blows in May and June 1771. But the outcome is not one we would have hoped for.

Government for North Carolinians in the backcountry of the late 1760s was centered in Hillsborough although populations lived as far west as Bethabara, Salisbury, and Mecklenburg County. The yeomen farmers of this region had been preyed upon and financially abused for years by authorities appointed by North Carolina’s royal governor and colonial assembly. These perpetrators were lawyers, clerks, sheriffs, judges, and tax collectors let loose upon the backcountry citizenry with scant oversight. The citizens, calling themselves Regulators, simply and deservedly, wanted a better regulation of government. They just wanted it to work like it was supposed to work.

These unrelenting abuses in time inspired riots in Hillsborough in September 1770 when Regulators attacked the courthouse, chasing Judge Richard Henderson from the bench and lawyers through the streets. As tensions between Regulators and officials continued through the winter, rather than address the honest concerns of these colonists, the Provincial Council called for an armed militia to advance into the backcountry in spring 1771 to squelch this uprising among frustrated citizens. And to let everyone know he was in-charge, Royal Governor William Tryon would lead them.

Royal Gov. William Tryon

Tryon had some trouble gathering a militia force. Many eastern farmers, siding with the Regulators, refused to muster, but the governor persuaded enough from the coastal plain counties with the offer of extra pay. These were North Carolina citizens, not British soldiers, and the eventual confrontation at the Battle of Alamance on May 16, 1771, was not the first battle of the American Revolution as some claim. It was a show of force by the colonial government ending in bloodshed and made worse by the arrogance of the governor and his eager accomplices.

William Tryon was more successful in adding to his forces militia officers and “gentleman volunteers,” who made up a tenth of this army. These were a who’s-who of those who would later dominate North Carolina’s list of patriots during the War for Independence. They would be Sons of Liberty and signers of associations, resolves, and constitutions; but in 1771, these men were prominent among the colonial elites active in putting down this protesting in the backcountry.

At the same time, General Hugh Waddell, a hero of the French and Indian War and one who had been active against the Stamp Act in 1766, gathered men for a flanking maneuver. He marched a separate militia force from Cape Fear into Mecklenburg County intending to approach Regulator country from the west. By the time he crossed the Yadkin River, he had gathered only 250 men, a third of those he had hoped for, even from Rowan, Tryon, Anson, and Mecklenburg counties. And resistance to his march went beyond just reluctance. On May 9, his camp was surrounded by 2,000 Regulators giving out Indian yells, unsettling Waddell’s men such that some went over to the Regulators and others retreated with Waddell across the Yadkin River to Salisbury. About this time, as well, three brothers of the White family from now-Cabarrus County were among a group who attacked supply wagons bringing gun powder from South Carolina for Waddell. This party of Regulators burned two wagons of powder and other supplies on the muster field at Phifer’s Mill.

Tryon and his militiamen marched into Hillsborough on Saturday, May 11, with plans to be there for a while. It was supposed he would remain into Monday to oversee the election of a replacement for an elected member of the colonial Assembly, Herman Husband, who had been declared an outlaw as he was a leader of the Regulators. But Tryon became anxious about an amassing of Regulators to his west. He marched out the next day into the heart of Regulator country, and by Monday evening was camped on the west bank of Great Alamance Creek.

Regulators began to amass opposite Tryon’s camp. The two groups eyed each other uneasily over a couple of days. On May 15, the Regulators sent a petition to Tryon’s camp imploring him to consider the honest concerns of his colony’s citizens rather than make war on them. In response, Tryon promised his answer by noon the next day. On Thursday, May 16, Tryon marched his men to within 300 feet of the Regulator camp, which then had grown to between 2,000 and 3,000 men. Three Regulators, men of note and honor including a Presbyterian minister, went to Tryon’s camp attempting to forestall any bloodshed. Tryon took them hostage and sent one Regulator back with his ultimatum to disperse. To make his point, Tryon soon brought one of the hostages to the front line, where the man was shot in view of the Regulators. Tryon then sent a sheriff to the Regulators to announce under the Johnston Riot Act that they must disperse within one hour. And one hour later, the royal governor ordered Col. James Moore to fire the cannon at the Regulators. The battle had begun.

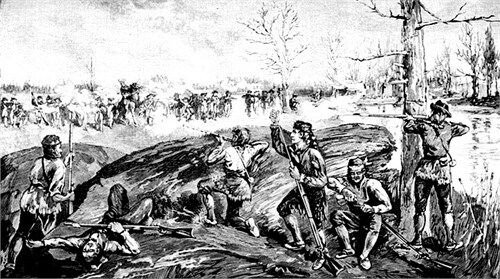

Battle of Alamance, May 16, 1771

Unfortunately, the Regulators were unprepared for a battle. Those with guns—and not all men present were armed—had brought only the supplies they might need for a hunt. Neither did they have leaders with military experience. The Regulators, firing from behind trees and rocks and fences, had initial success against the provincial militiamen standing in close order. But they soon ran low on ammunition and began to leave the field. Some were captured in their retreat by the pursuing militiamen.

On the morning after the battle, Tryon hanged prisoner James Few, age 25 and a new father of twins, on the battlefield without benefit of a trial. Tryon did this, perhaps, to intimidate his own provincial militiamen who might have had leanings in support of the Regulators. The number of men killed or wounded on both sides may have been around 150.

As horrible as the Battle of Alamance was, the real tragedy of the War of the Regulation unfolded through the remainder of May as Tryon and his army of militiamen and rangers marched west into the heart of Regulator country principally following the Indian Trading Path west toward Salisbury. He intended to punish those he saw as rising against his authority, especially seeking out the Quaker, Baptist, and Presbyterian communities which had suffered under the malfeasance of the officials and from which the Regulator Movement had sprung. Tryon’s army destroyed the homes, barns, and fields of James Hunter, a principal Regulator leader. The militiamen completely eradicated the 600-acre plantation of the absent Herman Husband. The militiamen confiscated 70 barrels of flour and commandeered scores of cattle from the communities for feeding the army. And Tryon set loose on the communities the much-despised Edmund Fanning who was bent on revenge against these Regulators, who had burned his house in Hillsborough.

Gov. Tryon confronting Regulators in Hillsborough, NC

By May 28, they crossed Deep River and on June 1 arrived at Jersey Settlement east of the Yadkin River not far from Salisbury. Turning north from there, this army of retribution marched toward Bethabara at today’s Winston-Salem. Along Abbotts Creek, they rousted Benjamin Merrill and his family from their beds, turned over his beehives and turned loose a hundred horses into his crops to forage. Merrill had led 300 Regulators toward Alamance Creek but had turned back upon learning of the battle. Others along Abbotts Creek had to supply 30 beeves and 20 more barrels of flour for feeding this militia army. Tryon continued his merciless spectacle of terrorizing citizens in the countryside by court-martialing some and subjecting them to public lashings. The prisoners he had taken at the battle and in his cross-country march were paraded along during this rampage, tied up two-by-two.

During this march, Tryon offered a pardon to those who would come in and take an oath of allegiance to the Crown even though no one was rebelling against British rule. In a few weeks, some 6,400 men—about three-quarters of the free, white males in the piedmont—did so, turning in their weapons such that Tryon had wagonloads of this booty hauled back to New Bern.

In early June, Tryon arrived at Bethabara, where the Moravians recorded in their journals that among the volunteers in Tryon’s army were “all the leading men of the country.” On June 4, Tryon’s army and the community celebrated the birthday of King George III, then age 33. Afterward, General Hugh Waddell marched his militiamen south intending to subdue Regulators in Tryon and Rowan counties. On June 9, Tryon announced his offer of a substantial reward of money and land for the return—dead or alive—of four named Regulators. He then marched his army and prisoners 85 miles over the next five days back to Hillsborough. When he arrived on Thursday, June 13, Tryon, a vindictive, arrogant man, ordered his men to destroy the farm of the parents of James Few, the Regulator he had hanged on the battlefield the month before.

Also upon his arrival in Hillsborough, Tryon received confirmation that he was to report immediately as the new governor of New York. Keeping this news to himself, he then hurried through the trials which began on Saturday, encouraging the judges—including Richard Henderson and Maurice Moore—to give guilty verdicts. By Tuesday, 12 men were found guilty of treason, all to be hanged.

Plaque at Alamance Battlefield

State Historic Site, NC

Tryon selected a hilltop east of the town as the site of execution set for Wednesday, June 19. The townspeople were compelled to witness the execution with soldiers gathered around the gallows and horsemen riding about to assure that the citizens kept back from the soldiers. The people gathered, hopeful that Tryon might yet pardon them all. To demonstrate his mercy and his power, Tryon commuted six of those death sentences, but he ordered the other six men to be publicly hanged, including Benjamin Merrill. Each was stood on a barrel, one at a time, with a noose around his neck. Each was given the opportunity for last words, and then the barrel was jerked away.

The next day, Tryon left his army in charge of Col. John P. Ashe, who would 18 years later preside over North Carolina’s adoption of the U.S. Constitution. Tryon departed Hillsborough for New Bern to begin packing for his June 30 move to New York. Not surprising, the much-despised Edmund Fanning went to New York as well, serving as William Tryon’s secretary and in time as surveyor general for the colony.

North Carolina’s new governor, Josiah Martin, arrived in August. During his excursions into the backcountry to understand better the people and their problems, he was persuaded of the egregious behaviors worked by certain officials upon the citizens. He ordered a reconciling of the books and revealed that sheriffs were in arrears to the colonial coffers some £66,000, which the sheriffs were then compelled to send forward.

Memorial in Hillsborough, NC, to the six Regulators hanged there June 19, 1771

It is a popular notion—and an incorrect one—that these Regulators came back a few years later and fought for independence against the British. Facts do not bear this out. Some did, of course, but thousands of these deeply religious former Regulators had taken an oath of allegiance to the Crown. Some despaired and left the colony. Others were exiled. Most remained, discouraged. By and large, the former Regulators harbored hatred most for the colonial elites and “gentlemen volunteers” who had marched against them. The former-Regulators resented these men of position and power and were not so eager to join in the revolution when these same men decided that North Carolina should break away from Great Britain. As a result, the War of the Regulation deeply divided North Carolinians. Some would fight as Whig rebels for independence and others as Tories to retain British governance in the colony. Still others, including Moravians, would seek to remain neutral.

And so it continued, setting the stage for the American Revolution to unfold in North Carolina. •

Source: Breaking Loose Together, Marjoleine Kars, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, 2002